Hidden Skodas: Unlocking the brand's secret museum room

"How much more time have you got?” asks Michal Velebný, Skoda Depository’s head honcho, while we stare at a near-perfect light-green 110 L Rallye that has just arrived from a life in Cyprus.

An intriguing question, and one to which I already know the answer as I look at the Czech Republic-based Skoda rep staring both at his watch and my way. “About five, maybe 10 minutes,” I lie – but it’s a fib I would not long regret.

Velebný ushers us out of his workshop and guides us through the underbelly of Skoda’s treasure-filled Mladá Boleslav museum – which, in the building of the car maker’s old factory, houses more than 300 cars and pre-Skoda Laurin & Klement bikes – to where a large wooden door stands.

A padlock is opened and we enter a vast room of scattered metal, representing the 118-year history of the Czech brand. This is a room not many, bar select staff, set foot in. Not even the flush delegates get a look in here. The dust backs that up.

“Sorry for the mess,” apologises Velebný, while pointing to a half-restored 1960s Formula 3 car and a covered-up, chrome grille-clad Popular Monte Carlo. Where we are standing is one of many rooms that make up Skoda’s depository, a collection of unique, classic and rare gems collected by the Czech manufacturer.

There are almost 250 cars housed within the museum (that number doesn’t include the vehicles on show in the main building), either polished up and on display in the prototypes and sports cars depository or wherever they can fit in the old museum and its outbuildings. So big is the collection that a further 80 cars are also stored off-site.

“This car we restored from a burnt-out chassis,” says Velebný, standing over one of two 1958 1100 Coupés. “The driver got out the back window after it crashed.” This one is fitted with a special 91bhp OHC engine – a once-feared 555kg sports car so beautifully designed that it could easily be badged by one of Italy’s finest.

Previously owned by Hanus Hrabánek, father of Skoda Motorsport director Michal Hrabánek, it is the only example that remains in a roadworthy state. Velebný was one of a few to lead the restoration from a fire-damaged wreck. “It is a special car,” he adds.

There is another car he is keen to show us: a 1928 Skoda Hispano-Suiza 25/100 KS. Limited to just 100 units worldwide, fitted with a 6.6-litre aircraft-derived six-cylinder engine and weighing in at around two tonnes, the monstrous-looking car – one of just a handful to have survived to this day – sits on a ramp in the corner of the room.

“It didn’t always look like this,” says Velebný, pointing at the car’s deep-blue colour, glistening chrome grille and near-perfect interior. “It was restored by the previous owner, who used a picture of another car [for reference] and everything was wrong: the shape of the bodywork, the colour of the bodywork, upholstery. It was an ugly car.”

This led Velebný to reveal his other passion for the job. “I call it archaeology,” he says, “when you have to try to make it look how it did before and look and search history to find concrete pieces about the cars. I love it. There are not many jobs that are also your hobby.”

On a mission to restore it “properly”, he set out on a demanding, multi-year project with the aim of returning the car to its original form. To do this, he started at the beginning and tracked down its first owner. “I searched and found the family, visited them, explained what I needed and they helped to trace their family and gave me access to their archives,” says Velebný.

“There were five huge boxes of small photographs, and in the end I found four pictures and one video. From that I got an impression of how the car looked from each angle, and I was able to completely restore it to its original ‘wow’ state.”

As Velebný’s stories reveal, this isn’t just a job for the Czech native – this is the life he was always destined to live, and for good reason. He comes from a long line of Skoda workers and is the third generation of Velebný – his son, currently studying engineering, is set to become the fourth – to be employed by the nation’s car maker.

But choosing to take a job in the depository 10 years ago, having been at the company since 1990, was a decision driven with family in mind.

“My grandfather, father and uncle, they built the history,” he says. “I’m now maintaining it.”

His grandfather Josef – who worked for the pre-Skoda-takeover Laurin & Klement from 1925 – was chief designer of bodywork between 1946 and 1966. He oversaw an array of revolutionary technological changes, from safer, more robust and more spacious all-metal bodies from the 1200 to the brand’s first monocoque chassis in the rear-engined 1000 MB.

The apple really didn’t fall far from the tree, as Josef’s two sons – Michal’s father Dusan and uncle Milan – joined the company in the early 1960s. Dusan, who was the owner of the other 1100 OHC Coupé, headed the testing centre of the Czech car maker’s Research and Development Institute, while Milan developed engines for the brand’s racing cars, from Formula 3 to the immortal 130 RS.

“You could say it runs in the family,” jokes Velebný, while standing in front of his grandfather’s signature, which adorns one of the museum’s walls.

In his role, the third-generation Velebný leads a team of five people at the depository: one engine specialist, two bodywork specialists and another two ‘hybrid’ specialists. “And me, the boss,” adds Velebný.

But for him, this is much more than a day job. “Of course,” he laughs when asked if he owns any classic Skodas himself. The list he rattles off doesn’t disappoint. In his five-car garage sits a Favorit Rally – currently being restored with his son – and a Skoda Formula 3 car which is “on the waiting list”.

But his prize possession is something of a gem: Skoda’s sole-running Le Mans car, which finished fifth in 1950’s 24-hour event. Adorned with the number 44, it has been fully restored by Velebný over six years, and he now campaigns it in the Le Mans Classic event each year. “Many projects,” he says. “It is like having my own museum at home, but there is not enough space!”

Back in the workshop, filled with period machinery used on a daily basis, we again look over the 110 L Rallye, today being readied for a special display at the museum. “This building is more than 100 years old,” says Velebný, pointing at the tattered walls and beamed ceiling. “We are restoring historic cars in a historic building.”

Skoda 1000MB

Skoda’s first mass-produced car could easily be billed as the Czech Ford Anglia. As well as being the debut for the brand’s new frameless platform (no more frame-on-chassis designs), the 1964 1000 MB was powered by a 36bhp 1.0-litre rear-mounted four-pot at a time when anything other than a front-mounted powerplant was rarely considered.

Sixty years on it can still eat up the miles, although too much speed tends to transfer weight to the rear and the steering becomes light. Quirky touches come in the form of a pre-EV-era ‘frunk’ and a grille that drops down to reveal a spare wheel.

Skoda Popular Monte Carlo

Just 10 of these grilled-light specials were built, and three remain. This late-1930s GT was commissioned following the brand’s second-place finish at the 1936 Monte Carlo Rally.

Fitted with independent suspension all round and a rear axle-mounted three-speed ’box, and sitting on a lightweight central tubular frame, the Monte Carlo was staggeringly smooth and capable for its age, albeit with a tad too much body roll. Its dual-clutch gearbox sent power from the very progressive 31bhp 1.4-litre four-pot to the rear wheels, all of which needed adjusting to for this used-to-modern-touches driver.

Special operations

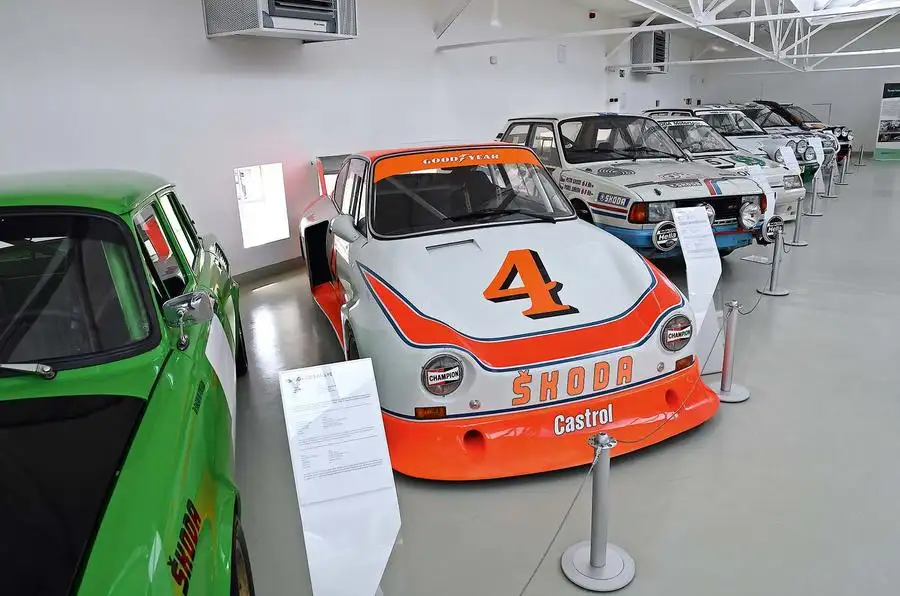

One of the most sought-after rooms to visit at the Mladá Boleslav museum is the prototypes and sports cars depository. Requiring a special key and even a guide to enter, it is a space filled with some of Skoda’s most iconic one-offs, concepts and treasured cars.

With a single aisle to walk down, you’re flanked by some of the brand’s unique creations, from concept-only cars such as the Joyster hatchback, to the first designs of the Roomster MPV and Yeti SUV.

A real one-off comes in the form of a true Hollywood D-lister: the Ferat vampire-mobile (above). A prototype of the never-released 110 Super Sport adapted for 1982 Czech horror flick Upír z Feratu (Ferat Vampire), it apparently runs on human blood and has a party trick that sees the whole passenger canopy, as well as the instrument unit, raise for entry.

Motorsport classics are also on display, from the storied Octavia WRC and Fabia WRC to the Porsche-aping 130 RS A5 and sleek Formula Skoda MTX 1-01. Other gems include the 110-based Buggy, which, back in the 1970s, was entered into exciting but short-lived Autocross Championships.

Verwandte Nachrichten