Of Blood and Fiberglass: The Insane Story Behind Fiberfab Kit Cars

"Is it real?" you might think to yourself. No way someone in your neighborhood has enough scratch to buy a timeless classic race car. But no, what sits before you is no Ford. It's a Fiberfab, whatever that means.

But the proverbial murder mystery behind the story of Fiberfab kit cars is so ludicrous that you could chalk it up to one of the craziest stories in automotive history. Not just of the latter 20th century but the entirety of it, full stop. In the same breath as anything nefarious that more modern boogiemen in the industry like John DeLorean or Carlos Ghosn, Fiberfab's leading man was a guy who left some real skeletons. In this case, that's not just hyperbole. But on the subject of Ghosn and Old Man DeLorean, Fiberfab's leading man, Warren "Bud" Goodwin, as you'll find, ironically shared qualities and quirks of both men.

But there wasn't much indication that the man who helped popularize fiberglass kit cars in North America would go on to be convicted of manslaughter for killing his wife. By all measures, Goodwin was a normal American boy. Born in 1921 to a British-born bakery manager father and a German immigrant mother in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Bud Goodwin had a fairly typical upbringing in the day for an American child of immigrants. Boyhood days spent attending school and playing baseball like most other kids were always peppered with another core memory for Goodwin, a lifelong love of fast cars.

In his adolescence, Goodwin moved with his family to the Detroit satellite city of Kenosha, Wisconsin. A place where hotshot auto manufacturers like Nash, Hudson, and later the fabled American Motors Corporation (AMC) produced millions of vehicles between the turn of the century and century's end. This close relationship between Kenosha and the American auto industry strengthened Bud Goodwin's resolve to join the scene one day, not as a designer of mass-market automobiles but purpose-built race cars.

Had Goodwin stayed in Wisconsin, that's probably where the story would've ended. But instead, Goodwin left his birth state for the hot-rodder paradise of Southern California. It wouldn't take long for Goodwin to integrate himself into the burgeoning So-Cal amateur racing scene soon after his relocation to Los Angeles around 1939. Around this time, American cars from Goodwin's childhood, like the iconic 1932 Ford family, were already taking on new life as hot-rods.

The drive to see who could shove the biggest engine under the hood and take first place at drag strips and dirt ovals across the continent became a defining characteristic of North American culture during the years leading up to and after World War II. If one could believe it, these LA-based impromptu racing series were often dominated not by domestic American iron but by imported British, Italian, and German machines. Less Ford, Chrysler, and General Motors and more Mercedes-Benz, Alfa Romeo, and Jaguar.

As alien as that might sound to modern Americans, these European cars' lightweight bodies and peppy little engines suited smaller circle tracks with shorter straightaways and circuit racing particularly well. It was at races of this variety that Bud Goodwin got his first taste of a formula that Lotus' old boss Colin Chapman described as "simplify, and add lightness." In 1955, Goodwin applied this philosophy to a home-built tube-steel race car with one huge quirk, a fiberglass body.

Fiberglass had only recently begun its ascent to a genuinely useful mass-produced construction material by the turn of the 1950s. Mass-market fiberglass material had only been discovered in the early 1930s and quite on accident, in fact, by a researcher employed by the Ohio-based Owens-Illinois glass company named Games Slayter. By aiming a blast of highly compressed air at a stream of molten-hot glass and capturing the resulting fibers into a tight weave bound by a plastic polymer, Slayter inadvertently created a compound that remained lightweight while holding just enough structural rigidity to make a passable auto-body.

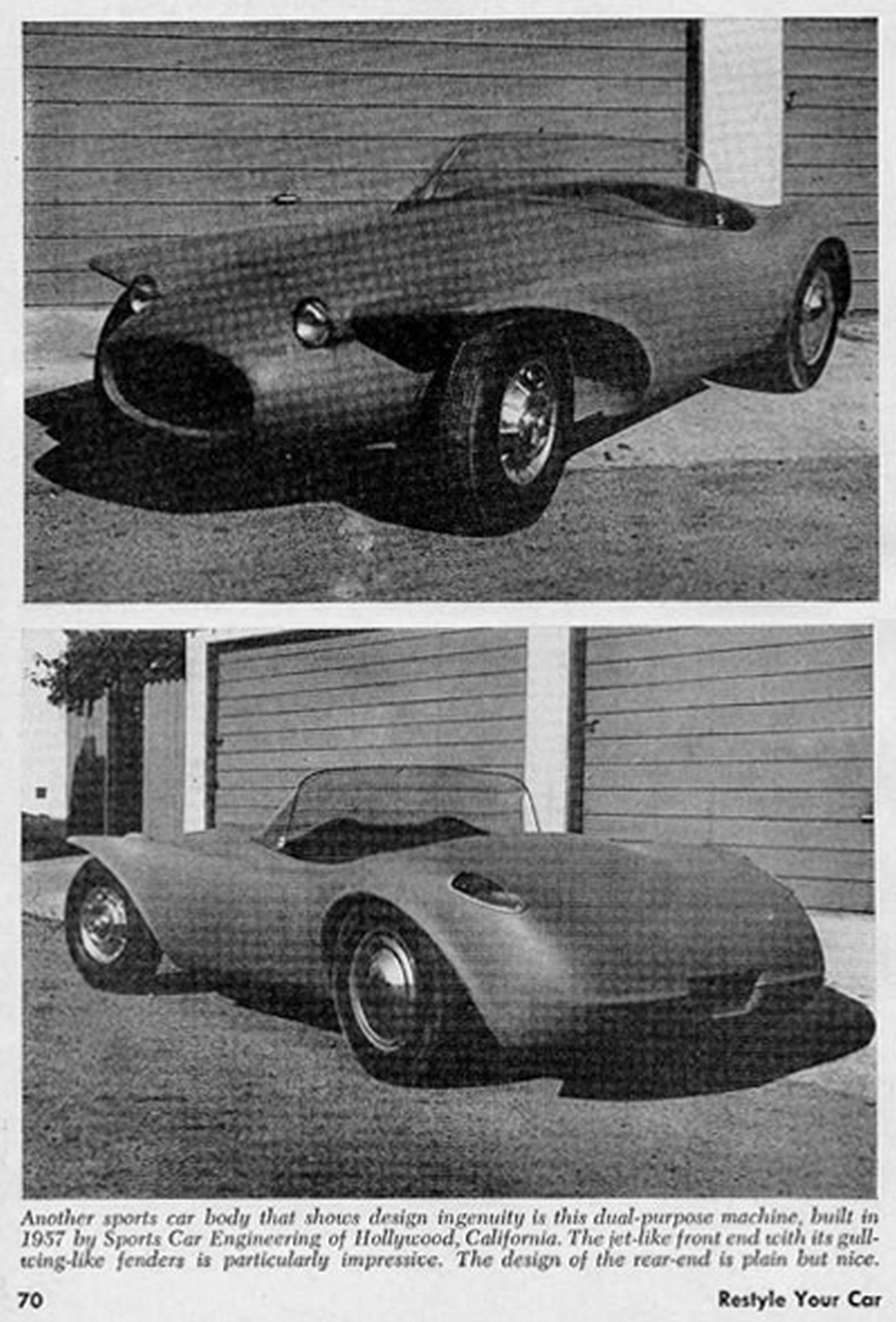

Bud Goodwin's first fiberglass race car from 1955 had a body straight from the factory of Microplas Limited in the West London suburb of Uxbridge. Hailing from their Mistral series of fiberglass sports cars, Warren Goodwin modified his race car to pair the fiberglass British body to the tube-steel frame of his own construction. The results were nothing short of immediate. By 1956, Goodwin was a mainstay of the Los Angeles gentleman's racer scene, and he was showing some serious driver skills and keen business acumen in the process.

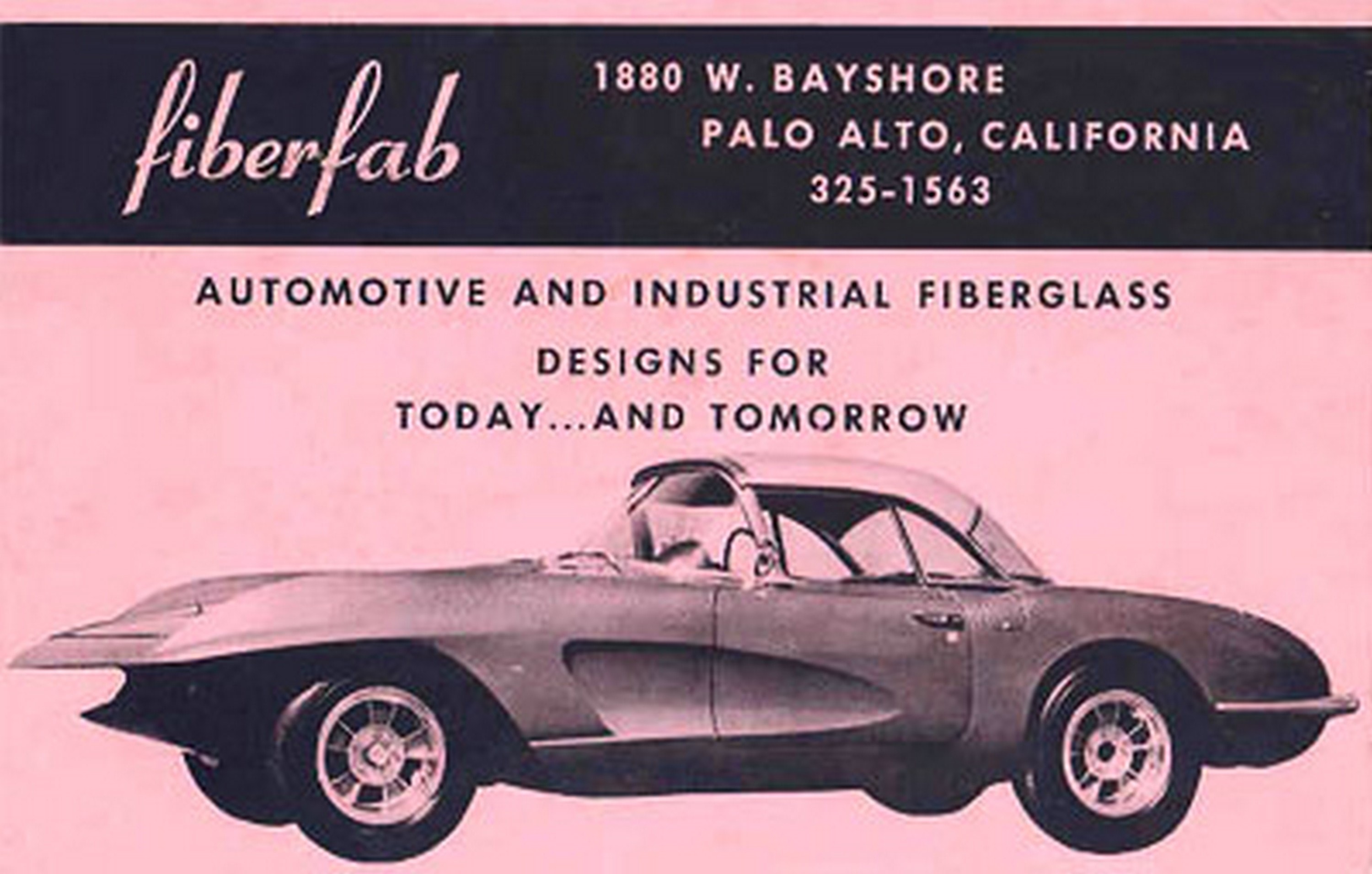

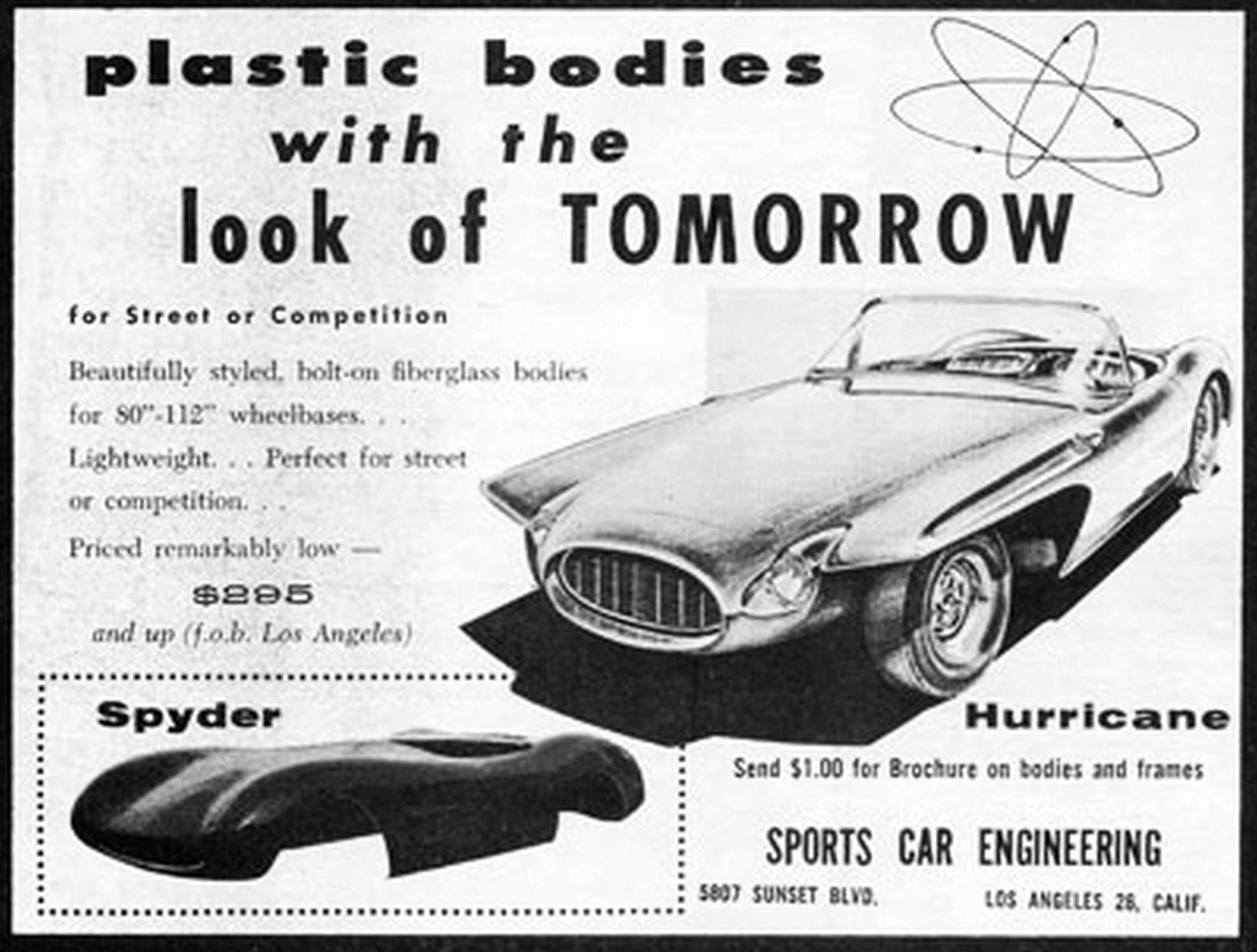

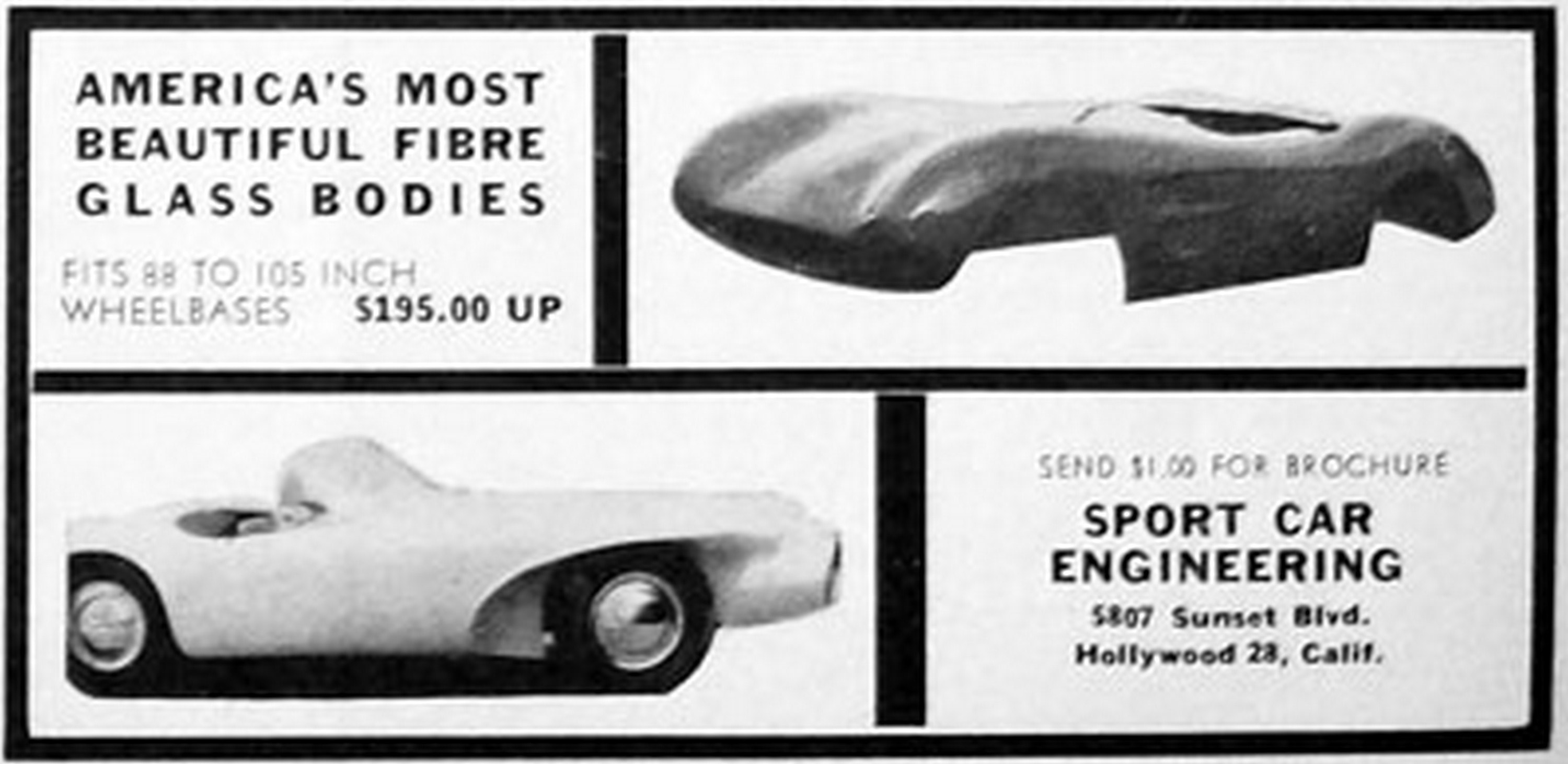

In September 1957, Goodwin incorporated his new company, Sports Car Engineering (SCE), with the Secretary of State in California. This firm would import and partially-built Microplas Mistral bodies and sell them to hot-rodders who were eager to take advantage of the V8 engine renaissance of the late 1950s. With Ford Y-blocks, small block Chevys, and Mopar HEMIs aplenty waiting for a lightweight racer to get shoved into across America, Goodwin re-named these Anglo-American racers to the "Spyder," under the SEC brand, to considerable fanfare.

With a price of $295 in late-50s money or a touch over $1,100 in 2024 cash for the most basic short-wheelbase Spyder, the bump up to $345 ($3,852 in 2024 money) for a slightly longer wheelbase wasn't too unreasonable. There was even the option for SEC to provide a similar tube-steel chassis to the one Bud Goodwin built when he first moved to So-Cal, along with the fiberglass British body, for $495 altogether ($5,527 in 2024 money). Keep in mind that the shortest wheelbase Spyder body only weighed around 100 lbs (45.35 kg).

With a bargain like that, Goodwin's company was well-suited to provide fiberglass bodies for track and street use that GI-billed ex-soldiers and the very earliest baby boomers of Southern California could spend their new-found cash on. The venture was so successful that Bud Goodwin was able to sell the SCE firm for a profit to the LA-based Du Crest Fiberglass company and walk away with enough cash to start another, larger fiberglass sports car outlet. By this time, the SCE body line had expanded to include two new sports car models, including the Tornado and the Hurricane.

In 1964, Goodwin met the man who'd helped him make lightning strikes twice, a man by the name of John Hebler. By trade, Hebler was an expert in plastic mold production. As the soon-to-be shop manager of Goodwin's new fiberglass outlet, it was Hebler's skill as a mold engineer, melded with Goodwin's knack for automotive design, that the duo hoped would bring unparalleled new success. Except, this wasn't just a duo. There was a third executive appointed for the automaker that'd come to be christened the Fiberfab Company. That being Goodwin's second wife, Jamaica Karen Goodwin, who would serve as the president and office head of staff and was 18 years Bud's junior.

Two years after going live in 1964, Fiberfab already produced a range of fiberglass sports car bodies. Designs like the hard-top coupe Apache built as a replacement body for C2 Corvette chassis, the Centurion, a replica of the late 50's XP-87 Corvette race car, and the Aztec, which resembled the famous Lola Mk6 racer with Volkswagen underpinnings, proved the short and chubby but furiously passionate Bud Goodwin might've not been the easiest person to work with. Still, he was damn good at designing kit cars. But of all of Fiberfab's models, it was the Valkyrie that made the most headlines.

Styled as a tribute to the Ford GT40, which was actively attempting to spite Enzo Ferrari's ambitions at LeMans at the time, the Valkyrie could be bought as a ready-to-race completed with a 427 cubic inch Ford V8 and a five-speed ZF gearbox or as a kit car. With bits and pieces of Chevy Corvair hardware underneath in the form of the front sub-frame and the steering box, components of this fiberglass race car could be repaired by average mechanics used to working on Ford or Chevy products of the day.

At $1,495 for the bare body shell alone ($14,448 in 2024), most people opted to build their Valkyries instead of shelling $12,500 ($120,804 in 2024) for a full-assembled turn-key racer. Though not quite a sales bonanza, the Valyrie was much respected in the sports car and racing communities, netting third place in the prototype section of the 1967 New York International Sports Car Show.

The Valkyrie was flanked by the rear-engined Avenger GT, similarly shaped to the Valkyrie but with mounting points for the engine in the rear rather than the middle. That same year, in 1966, Goodwin founded another company, Velocidad Inc., making Fiberfab a wholly-owned subsidiary with plans to expand production across the border in Mexico and nearby Santa Clara.

For Fiberfab, the exposure could've served as the secret sauce that helped Bud Goodwin's personal ambitions expand further. At least, it would have had a shocking turn of events not occurred. In 1967, police raided Goodwin's luxurious mountain-top house in Los Gatos, California, and arrested him on suspicion of murdering his wife, Jamaica. So reports published by the San Mateo Times detail that Goodwin is believed to have entered the home around 1 a.m. only to find another man, reported to be a family friend, sitting on the couch with his wife.

In a rage that some believe was the culmination of years of attitude problems, stress, and bad blood related to the tribulations of running Fiberfab, Bud Goodwin completely snapped. He proceeded to brandish a semi-automatic pistol and fire a warning shot over the heads of both the man and his wife, but an accidental second discharge of the gun fatally wounded Jamaica Goodwin. With all the evidence presented in court, it was nothing short of damning for the notoriously hot-headed elder Goodwin.

Bud Goodwin was convicted of voluntary manslaughter and sentenced to a one-year stint in the county jail, avoiding a brutal and lengthy stint in California's notorious state penitentiaries by proving that he never intended to murder Jamaica, only to menace her and for her perceived unfaithfulness in a state of unhinged paranoia. But prison justice didn't come to Goodwin in the typical form of a few butt kickings and inmates spitting in his chow-hall tray. Instead, Goodwin was found dead of a heart attack in his jail cell on December 26th, 1968.

All the while, Fiberfab managed to carry on despite John Hebler, the company's arguable heart and soul, taking his leave soon after Bud Goodwin's untimely demise. Fiberfab underwent two corporate takeovers during the 1970s, first to Concept Design America Ltd, a company run in part by Goodwin's old plant manager, Richard Figueroa, and again in 1974, this time to the Pennsylvania-based A.T.R. Inc. In that time, the firm continued to design new kit car bodies with even bolder, more raidcal styling cues. Derivatives and spinoffs of these kits proliferated across the globe from the US to the UK, Germany, Canada, and even Brazil, far too many to name in one sitting.

In 1979, Fiberfab left California for Minneapolis, Minnesota, where it was taken over once again by the rival fiberglass auto body maker Classic Motor Carriages, makers of the famous retro-styled Gazelle luxury sports car. But it seemed that controversy couldn't help but find its way to Fiberfab, and CMC was forced to cease operations in 1994 after the Florida Attorney General issued a lawsuit on behalf of at least 900 of CMC's customers, citing safety and build quality concerns.

Nine years later, another firm out of La Pine, Oregon, purchased the IP rights to Fiberfab with the intention of starting Valkyrie production once again in 2004. Since 2003, the project website has remained dormant and un-updated for over twenty years, seemingly stricken by some automotive hex that's followed the Fiberfab name since Bud Goodwin fired that fatal shot.

Like John DeLorean, Goodwin may have been a profoundly talented designer with an endearing knack for entrepreneurship. But like Carlos Ghosn, the bad side eventually outweighed the good in the end. As a cautionary folk tale told through the lens of the automotive, there might not be a better one out there.